Myxomatosis in rabbits

Esther van

Praag, Ph.D.

|

MediRabbit.com is

funded solely by the generosity of donors. Every

donation, no matter what the size, is appreciated and will aid in the

continuing research of medical care and health of rabbits. Thank you |

Warning: this file contains pictures that may be distressing to some persons

Sanarelli

first recognized the myxomatosis disease in 1896, in Uruguay, where it causes

sporadic lethal infections in the American cottontail species (Sylvilagus

sp.). The virus has spread over the entire American continent, and has become

endemic in some regions (Chili, in O. cuniculi; Western USA, in Sylvilagus

bachmani).

It was soon discovered that the

European rabbit, (Oryctolagus cuniculi) was very sensitive to this

virus, causing severe skin abscesses, infections, and ultimately death. In the

1950se, the myxomatosis virus was introduced and spread among wild rabbits in

Australia, in order to reduce its population. This operation decimated almost

all the wild rabbit population, except a few individuals that seemed

resistant to this virus. The surviving rabbits started to reproduce offspring

and colonized the country anew. In Europe, the virus spread rapidly and has

now become endemic in some regions, which are populated by the European

rabbit.

The

lagomorph’s groups largely affected by the myxoma virus are the European

rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculi), the European hare (Lepus europaeus),

the Brush cottontail (S. bachmani) and the eastern cottontail (S.

floridanus).

Myxomatosis

is caused by a virus belonging to the family of the Poxviridae, and is a type

species of the genus Leporipoxvirus. The later comprises close related

viruses that affect he American cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus sp.) and

the “hare fibroma virus”, among others. All these viruses lead to the

development of tumors of the skin connective tissues (fibroma). Various

strains exist. Some are very virulent (e.g. Standard laboratory, Lausanne,

California), others manifest their presence chronically. Genetic

studies show a relationship between the myxoma and the Shope fibroma virus Blood sucking insects (fleas, mosquitoes, lice and

mite) are efficient mechanical vectors of this disease. It was observed that

the virus is present in the mouth’s parts of the rabbit flea Spilopsyllus

cuniculi, where it can survive over 100 days, independently of the

environmental conditions. It is furthermore speculated that the disease may

spread from one rabbit to another during skin and fur contact.

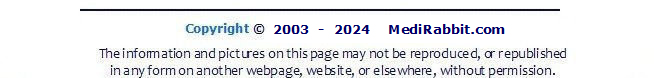

Clinical signs

The

development of myxomatosis follows the typical pattern of a poxvirus infection.

Once inoculated in the skin, the virus starts to reproduce in the skin and

local lymph nodes. The virus is then spread through the body. The viruses are

then spread throughout the body (viremia) and into the skin.

The

first evident signs of the disease appear 3 days after the infection:

swelling (edema) of the eyelids, followed by the lips, genital organs and

purulent conjunctivitis. At later stages of the disease, the rabbit becomes

blind. The disease is usually fatal between day 8 to

15 after the infection with the virus.

In

the chronic form of the disease, the most prominent signs are the formation

of skin tumors, called myxoma, on the ears, nose and limbs. These tumors will

resorb by themselves after some time.

A

side effect of the chronic form of myxomatosis is the development of

secondary bacterial infection. Pneumonia caused by Pasteurella sp. or Staphylococcus

aureus is often observed. It is accompanied by respiratory distress

(dyspnea).

Diagnosis

Although

the disease depends on the strain of myxoma virus, it is usually severe and

almost always fatal. The

clinical symptoms are sufficient for diagnosis. One must keep in mind though,

that early stages of the spirochetosis disease (caused by the parasite Treponema

sp., affecting the perianal parts of the rabbit) look similar to those of

myxomatosis. Indeed, tumors of those diseases show close similarities, so

spirochetosis and myxomatosis must be carefully differentiated from each

other. Myxomatosis

should furthermore be differentiated from an upper respiratory infection,

like e.g. Pasteurellosis. In the later, no swelling is observed in the

perianal region, on the contrary to myxomatosis. In the

case myxomatosis is chronic, it is recommended to do a biopsy and check it

for the presence of viruses. Treatment

If a rabbit is affected by the aggressive form of myxomatosis, its

chances of survival are close to zero. It is then recommended to humanely put

the affected animal to sleep. If treatment is chosen, intensive care over a longer period of time is

needed. It is important to keep the sick rabbit in a warm environment

(21-22°C). Eyes and ears must be regularly cleaned. As much fluids and food

should be given to the rabbit as possible, even if the rabbit is drinking

good amounts of water by itself. Skin tumors can be removed surgically. Unfortunately, secondary complications often appear. The most common

one are respiratory disease and pneumonia, due to secondary infection by Pasteurella

sp. or Staphylococcus sp. Rabbit that suffer a chronic form of myxomatosis recover by

themselves. Antibiotics can be given to avoid respiratory complications. In regions where myxomatosis is endemic and present among the wild

rabbit or cottontail population, prevention of the disease in pet rabbits is

is possible by regular vaccination. This is not available in all countries.

Depending

on the vaccine used and the age or breed of rabbits, vaccinated rabbits may

develop a mild to serious form of the disease. In rare cases, the rabbit must

be put to sleep.

For detailed information on myxomatosis in rabbits,

by E. van Praag, A. Maurer and T.

Saarony, 408

pages, 2010. Acknowledgement

A special thanks to Denise Baart, for

sharing the pictures of her rabbit Bucks. Further Reading

Best SM, Collins SV, Kerr PJ.

Coevolution of host and virus: cellular localization of virus in myxoma virus

infection of resistant and susceptible European rabbits. Virology. 2000;

277(1):76-91. Boag B. Observations on the

seasonal incidence of myxomatosis and its interactions with helminth parasites

in the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). J Wildl Dis. 1988;

24(3):450-5. Boag B, Lello J, Fenton A,

Tompkins DM, Hudson PJ. Patterns of parasite aggregation in the wild European

rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Int J Parasitol. 2001; 31(13):1421-8. Calvete C, Estrada R, Villafuerte

R, Osacar JJ, Lucientes J. Epidemiology of viral haemorrhagic disease and

myxomatosis in a free-living population of wild rabbits. Vet Rec. 2002;

150(25):776-82. Chapple PJ, Lewis ND. Myxomatosis

and the rabbit flea. Nature. 1965; 207(995):388-9. Chapuis JL, Chantal J, Bijlenga G.

Myxomatosis in the sub-antarctic islands of Kerguelen, without vectors,

thirty years after its introduction. C R Acad Sci III. 1994; 317(2):174-82. Duclos P, Caillet J, Javelot P. Aerobic

bacterial flora of the nasal cavity of rabbits. Ann Rech Vet.

1986; 17(2):185-90. Edmonds JW, Nolan IF, Shepherd RC,

Gocs A. Myxomatosis: the virulence of field strains

of myxoma virus in a population of wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus

L.) with high resistance to myxomatosis. J Hyg (Lond). 1975; 74(3):417-8. Flowerdew JR, Trout RC, Ross J.

Myxomatosis: population dynamics of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus

Linnaeus, 1758) and ecological effects in the United Kingdom. Rev Sci

Tech. 1992; 11(4):1109-13. Fountain S, Holland MK, Hinds LA,

Janssens PA, Kerr PJ. Interstitial orchitis with impaired steroidogenesis and

spermatogenesis in the testes of rabbits infected with an attenuated strain

of myxoma virus. J Reprod Fertil. 1997; 110(1):161-9. Ghram A, Benzarti M, Amira A,

Amara A. Myxomatosis in Tunisia: seroepidemiological study in the Monastir

region (Tunisia). Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 1996; 73(3-4):167-72. Gorski J, Mizak B, Chrobocinska M.

Control of rabbit myxomatosis in Poland. Rev Sci Tech. 1994; 13(3):869-79. Jiran E, Sladka M, Kunstyr I.

Myxomatosis of rabbits--study of virus modification. Zentralbl Veterinarmed

B. 1970; 17(3):418-28. Joubert L, Tuaillon P, Larbaigt G.

Serologic and allergologic relationship between rabbit myxomatosis and

fibromatosis viruses. Conglutination reaction and homologous and heterologous

hypersensitivity. Bull Acad Vet Fr. 1970; 43(6):259-76. Joubert L, Oudar J, Mouchet J,

Hannoun C. Transmission of myxomatosis by mosquitoes in Camargue. Preeminent

role of Aedes caspius and Anopheles of the maculipennis group.

Bull Acad Vet Fr. 1967; 40(7):315-22. Kerr PJ, Merchant JC, Silvers L,

Hood GM, Robinson AJ. Monitoring the spread of myxoma virus in rabbit Oryctolagus

cuniculus populations on the southern tablelands of New South Wales,

Australia. II. Selection of a strain of virus for release. Epidemiol Infect.

2003; 130(1):123-33. Kerr PJ, Best SM. Myxoma virus in

rabbits. Rev Sci Tech. 1998; 17(1):256-68. Lawton MP. Myxomatosis vaccine.

Vet Rec. 1992; 130(18):407-8. Licon Luna RM. First report of

myxomatosis in Mexico. J Wildl Dis. 2000; 36(3):580-3. Marcato PS, Simoni P.

Ultrastructural researches on rabbit myxomatosis. Lymphnodal lesions. Vet

Pathol. 1977; 14(4):361-7. Marlier D, Mainil J, Linde A,

Vindevogel H. Infectious agents

associated with rabbit pneumonia: isolation of amyxomatous myxoma virus

strains. Vet J. 2000; 159(2):171-8. Merchant JC, Kerr PJ, Simms NG,

Robinson AJ. Monitoring the spread of myxoma virus in rabbit Oryctolagus

cuniculus populations on the southern tablelands of New South Wales,

Australia. I. Natural occurrence of myxomatosis. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;

130(1):113-21. Merchant JC, Kerr PJ, Simms NG,

Hood GM, Pech RP, Robinson AJ. Monitoring the spread of myxoma virus in

rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus populations on the southern tablelands of

New South Wales, Australia. III. Release, persistence and rate of spread of

an identifiable strain of myxoma virus. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;

130(1):135-47. Nash P, Barrett J, Cao JX,

Hota-Mitchell S, Lalani AS, Everett H, Xu XM, Robichaud J, Hnatiuk S, Ainslie

C, Seet BT, McFadden G. Immunomodulation by viruses: the myxoma virus story.

Immunol Rev. 1999; 168:103-20. Omori M, Banfield WG. Shope

fibroma and rabbit myxoma factories: electron microscopic observations. J

Electron Microsc (Tokyo). 1970; 19(4):381-3. Patterson-Kane J. Study of

localised dermatosis in rabbits caused by myxomatosis. Vet Rec. 2003;

152(10):308. Patton NM, Holmes HT. Myxomatosis

in domestic rabbits in Oregon. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1977; 171(6):560-2. Regnery DC. The epidemic potential

of Brazilian myxoma virus (Lausanne strain) for three species of North

American cottontails. Am J Epidemiol. 1971; 94(5):514-9. Regnery DC, Miller JH. A myxoma virus

epizootic in a brush rabbit population. J Wildl Dis. 1972; 8(4):327-31. Robinson AJ, Muller WJ, Braid AL,

Kerr PJ. The effect of buprenorphine on the course of disease in laboratory

rabbits infected with myxoma virus. Lab Anim. 1999; 33(3):252-7. Ross J. Myxomatosis and the

rabbit. Br Vet J. 1972; 128(4):172-6. Ross J, Tittensor AM. The

establishment and spread of myxomatosis and its effect on rabbit populations.

Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986; 314(1167):599-606. Ross J, Sanders MF. The development

of genetic resistance to myxomatosis in wild rabbits in Britain. J Hyg

(Lond). 1984; 92(3):255-61. Ross J, Tittensor AM, Fox AP,

Sanders MF. Myxomatosis in farmland rabbit populations in England and Wales.

Epidemiol Infect. 1989; 103(2):333-57. Ross J, Sanders MF. Changes in the

virulence of myxoma virus strains in Britain. Epidemiol Infect. 1987;

98(1):113-7. Rothschild M. Myxomatosis and the

rabbit flea. Nature. 1965; 207(2):1162-3. Sellers RF. Possible windborne

spread of myxomatosis to England in 1953. Epidemiol Infect. 1987

Feb;98(1):119-25 Shepherd RC. Myxomatosis: the

occurrence of Spilopsyllus cuniculi (Dale) larvae on dead rabbit

kittens. J Hyg (Lond). 1978; 80(3):427-9. Shepherd RC, Edmonds JW.

Myxomatosis: the release and spread of the European rabbit flea Spilopsyllus

cuniculi (Dale) in the Central District of Victoria. J Hyg (Lond). 1979;

83(2):285-94. Sobey WR, Conolly D, Haycockp,

Edmonds JW. Myxomatosis. The effect of age upon survival of wild and domestic

rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) with a degree of genetic resistance

and unselected domestic rabbits infected with myxoma virus. J Hyg (Lond).

1970; 68(1):137-49. Sobey WR, Conolly D. Myxomatosis:

passive immunity in the offspring of immune rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus)

infested with fleas (Spilopsyllus cuniculi Dale) and exposed to myxoma virus.

J Hyg (Lond). 1975; 74(1):43-55. Torres JM, Sanchez C, Ramirez MA,

Morales M, Barcena J, Ferrer J, Espuna

E, Pages-Mante A, Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. First field

trial of a transmissible recombinant vaccine against myxomatosis and rabbit

hemorrhagic disease. Vaccine. 2001; 19(31):4536-43. Trout RC, Ross J, Fox AP. Does

myxomatosis still regulate numbers of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus

Linnaeus, 1758) in the United Kingdom? Rev Sci Tech. 1993; 12(1):35-8. Werffeli F. Observations on the

appearance of a clinically atypical manifestation of myxomatosis in wild and

domestic rabbits. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 1967; 109(1):9-16. Williams RT, Dunsmore JD, Parer I.

Evidence for the existence of latent myxoma virus in rabbits (Oryctolaqus

cuniculus (L.)). Nature. 1972; 238(5359):99-101. Wunderwald C, Hoop RK, Not I,

Grest P. Myxomatosis in the rabbit. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2001;

143(11):555-8 Zuniga MC.

Lessons in D tente or know thy host: The immunomodulatory gene products of

myxoma virus. J Biosci.

2003; 28(3):273-85. |

e-mail: info@medirabbit.com