Myiasis

(fly-strike) in Rabbits

Esther van Praag Ph.D.

MediRabbit.com is

funded solely by the generosity of donors.

Every

donation, no matter what the size, is appreciated and will aid in the

continuing research of medical care and health of rabbits.

Thank you

|

Warning: this file

contains pictures and videos that may be distressing for people.

Myiasis, also called fly-strike,

is more frequently observed during the hot humid summer months. It is caused

by several kinds of insects that lay their eggs in the wounded skin of

mammals. Rabbits suffer in particular from the blowflies Lucilia sericata,

Calliphora sp., the grey flesh fly Wohlfahrtia sp., the common

screwworm fly Callitroga sp., and from the botfly Cuterebra sp,

which is seen in the USA only. A maggot attack is often linked to poor

hygiene, with rabbits kept on litter soiled with urine and excrements, or

poor-cleaned litter pans, but can also relate to health problems. A

particular attention must also be given to rabbits suffering from dental

(malocclusion, removal of incisors) or digestive diseases, from obesity,

untreated infected wounds, or that are disabled (fracture of the spine, limb,

arthritis, spondylosis). Indeed, the inability to groom the perianal and tail

regions, or eat their cecotropes feces can lead to the appearance of a smell

that will inevitably attract flies.

Myiasis flies lay eggs in the

skin soiled with feces or diarrhea, on skin irritated by urine or in

untreated infected wounds. The larvae that emerge from the hatched eggs will

immediately start burrowing themselves through the skin, into the flesh of

the host animal. A consequence is septicemia and shock, which lead to the

rapid death of the rabbit.

The

use of prophylactic solutions is not recommended as adverse fatal effects

have been observed in rabbits (Frontline). Some veterinary professionals use

the prophylactic product Dicyclanil (Novartis), which protects sheep against

the blowfly Lucilia sp. The product is not registered for use in

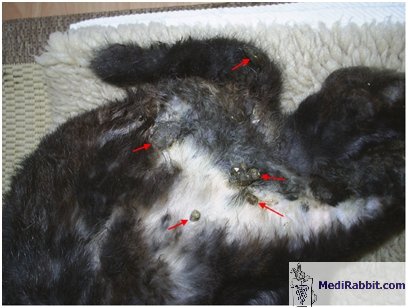

rabbits, and a safe use in rabbits can thus not be guaranteed. Clinical signsThe

early stages of myiasis are often subclinical. With time, a rabbit becomes

depressed, weak, loses weight and shows paresis. At this stage, the infection

becomes visible; the larvae are about 1 cm long and their hind part

protruding from the respiratory hole (spiracle) in

the skin.

In

a severe case, alopecia is observed. The skin is inflamed, injured with signs

of necrosis, and is often accompanied by the smell of ammonia. The later is

excreted by the larvae, in order to cause cell death

and decomposition, will cause an intoxication of the rabbit.

Aberrant migration of the larvae

is possible. Migration into the trachea has been observed. This leads to the

formation of a laryngeal edema, blocking the air supply to the lungs. It may

be accompanied by concurrent accumulation of mucus and swelling of the

esophagus.

Diagnosis

The history of the rabbit and the

clinical signs are generally sufficient for a proper diagnosis.

Treatment

The hair is delicately clipped away around the infected area and each

larva is removed individually and entirely with the aid of forceps, without

crushing it, to prevent skin irritation or the development of an allergic

reaction. The wounds are cleaned with a sterile saline solution, an

antiseptic solution (e.g. povidone-iodine or chlorhexiderme). There is no

need to use an insecticidal solution, if all the maggots have been removed.

• Injection of ivermectin (0.4 mg/kg, SC). The

rabbit must be closely monitored as the dying larvae excrete a toxin that can

be fatal to animals, including rabbits. Although controversial,

corticosteroids are sometimes given to the affected animal, in order to

reduce the swelling. • Injection of doramectin (0.5 mg/kg, SC). • Surgical removal, under anesthesia, in case of

aberrant migration or infection by Cuterebra sp.. Use of antibiotics is indicated, if the myiasis infection is severe.

They help fight a secondary bacterial infection of the wounds and prevent

sepsis, which can be fatal in rabbits. The administration of non-steroidal pain medication is necessary (e.g.

meloxicam, carprofen). When the affected rabbit has stopped to eat, it must be hand-fed and

given SC fluid therapy, in order to avoid the onset of fatal hepatic

lipidosis and dehydratation. Depending on the situation, the affected rabbit

can furthermore be administered appetite stimulants, or gut motility

medication (e.g. cisapride, metoclopramide). Bathing the rabbit with antiseptic or insecticide solution is not

indicated. This procedure is stressful for the rabbit, and often ends in a

panic reaction as soon as the fur is wetted or death by heart-arrest. A jump

out of the bathtub has led to broken limbs or fracture of the spinal cord. If

this method is nevertheless chosen, the rabbit should be dried with a towel

and a hair-dryer or placed under a heat lamp. The heat will indeed bring the

remaining worms to the surface of the skin, from where they can be easily

discarded. If a rabbit is heavily affected by myiasis,

euthanasia should be considered. Prevention of myiasis can be done

by addressing the causes of fecal or urine contamination of the skin, and by

keeping the rabbit in a clean hygienic environment. Daily inspection of the

perianal region is necessary in rabbits prone to suffer from digestive disorders,

that are obese or that are disabled. The fur should be combed with a

flea-comb, in order to detect the eventual presence of eggs and/or maggots.

The windows of the apartment or the cage of the rabbit can furthermore be

covered with a mosquito net, in order to avoid the insects to have contact

with the rabbit. For detailed information on fly strike infestation

in rabbits, see: “Skin Diseases of Rabbits” by E. van Praag, A. Maurer and T.

Saarony, 408 pages, 2010. Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Kerry Su-Lin Leow (Singapore) for

sharing her pictures. Further ReadingsBaird CR. Biology of Cuterebra lepusculi Townsend (Diptera:

Cuterebridae) in cottontail rabbits in Idaho. J Wildl Dis.

1983;19(3):214-218. Harcourt-Brown F.: Textbook of Rabbit Medicine. 1st ed.,

Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, England, 2002. Hess L. Dermatologic diseases. In: Ferrets Rabbits and Rodents.

Clinical Medicine and Surgery, 2nd ed., (Quesenberry K.F., Carpenter J.W.)

Saunders, St-Louis, USA., 2004. Jacobson HA, McGinnes BS, Catts EP. Bot fly myiasis of the cottontail

rabbit, Sylvilagus floridanus mallurus in Virginia with some biology

of the parasite, Cuterebra buccata. J Wildl Dis. 1978;14(1):56-66. Newell GB. Dermal myiasis caused by the rabbit botfly (Cuterebra sp). Arch Dermatol.

1979;115(1):101. Schumann H, Schuster R, Lange J. The warble fly Oestromyia

leporina (Diptera, Hypodermatidae) as a parasite of the wild

rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Angew Parasitol. 1985;26(1):51-52. Weisbroth SH,

Wang R, Sacher S. Cuterebra buccata: immune response in myiasis of domestic

rabbits. Exp Parasitol. 1973; 34(1):22-31. |

e-mail: info@medirabbit.com