Protozoal enteritis: Coccidiosis

Esther van Praag, Ph.D.

|

MediRabbit.com is funded solely by the generosity of donors. Every donation, no matter what the size, is appreciated and will aid in the continuing research of medical care and health of rabbits. Thank you |

Warning: this file contains pictures that may be distressing for some persons.

|

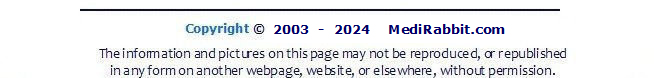

Coccidiosis is a highly contagious protozoan infection in rabbits with a low prognosis for recovery. It is caused by a protozoan parasite, Eimeria sp., and as many as 25 species of coccidia have been observed in the rabbit's gastrointestinal tract. However, it should be noted that in some cases, one coccidia has been given several names. Eimeria sp. parasites exhibit a high degree of specificity for a particular host, organ, or tissue, and they rarely pose a zoonotic threat to humans.

Rabbits that are healthy can act as asymptomatic "carriers" of the protozoa. The oocysts (eggs) shed with their feces can contaminate the environment, food, and water. Although the disease occurs primarily in intensively managed animals, especially younger ones, it also affects well-cared-for rabbits. To prevent the spread of coccidiosis, it is essential to maintain high standards of hygiene. This includes providing dry pellets instead of moist pellets, washing fresh vegetables, and ensuring access to ample fresh water. By adhering to these practices, the risk of coccidiosis can be mitigated. In the event that multiple rabbits are housed together, it is advisable to either refrain from placing food on the ground or to allow several rabbits to consume each other's soft cecotrophes. The parasite has a 4- to 14-day life cycle. It begins when food contaminated by oocysts is ingested orally. The oocyst wall is broken down in the stomach, and spores are released. The presence of biliary and pancreatic enzymes in the duodenal portion of the intestine stimulates the spores.

After entering the cells lining the intestinal wall, the spore will begin the asexual division process, known as schizogony, which occurs in one or more stages. The "merozoites," a stage of development, will then be released to infect other cells in the intestinal mucosa. The final stage of schizogony results in the formation of gametes, enabling sexual reproduction. Oocytes are shed in the feces. Asexual and sexual stages differ in terms of their location, organ- and tissue-specific characteristics. The presence of coccidia has been shown to affect the function of the host cell, with some cells exhibiting signs of inhibition and others displaying signs of hypertrophy. The development of induced villi atrophy can lead to a variety of health complications, including malabsorption of nutrients, electrolyte imbalance, anemia, hypoproteinemia, and dehydration due to epithelial erosion and ulceration.

Clinical signsThe severity of coccidiosis depends on the number of ingested oocytes. Clinical signs include reduced appetite, depression, abdominal pain, and pale, watery mucous membranes. However, these signs can be absent in older rabbits. Inspection of the feces often reveals blood and threads of mucus. Young rabbits present with retarded growth due to side effects on the kidneys and the liver in particular. Hematological studies indicate a decrease in hemoglobin and RBC count, along with a notable increase in PCV and total WBC. Serum analysis reveals reduced levels of sodium and chloride, with elevated potassium levels. This electrolyte imbalance can be attributed to diarrhea. Serum calcium, iron, copper, zinc, and glucose levels are often slightly lower compared to healthy animals, suggesting malnutrition due to intestinal damage or secondary bacterial infection. Liver coccidiosis is accompanied by significant elevation of serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT). Values return to normal after appropriate treatment. See: Clinical blood biochemistry of the rabbit Intestinal coccidiosis Intestinal coccidiosis, another form of the disease, primarily affects young rabbits between six weeks and five months of age. The condition is associated with stress, noise, transportation, or immunosuppression. It is most commonly observed in young, recently weaned rabbits, but it also affects older rabbits.

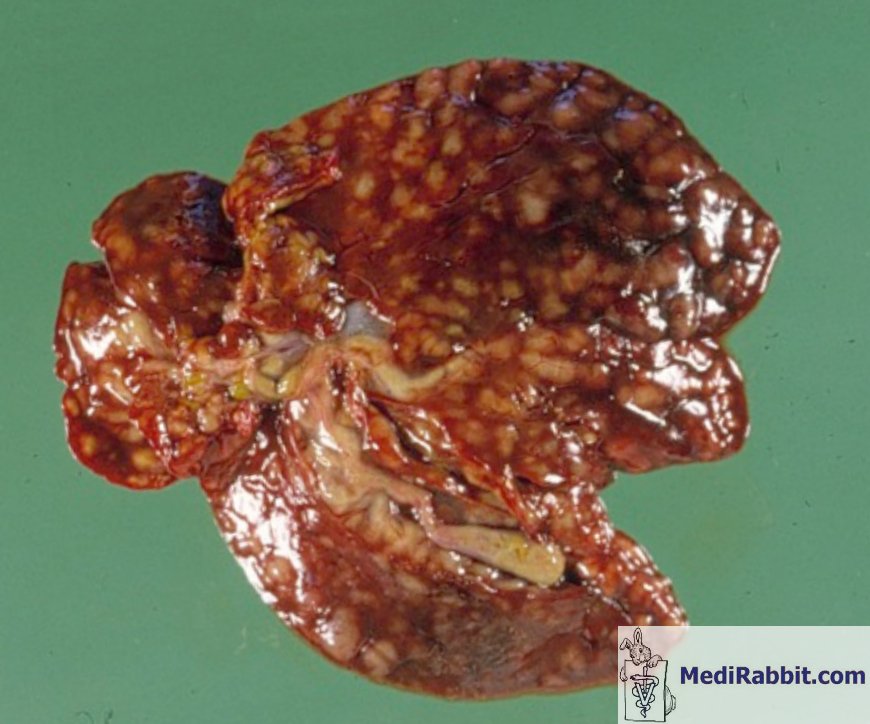

The clinical signs that appear 4 to 6 days after infection include a rough coat, dullness, decreased appetite, dehydration, and loss of weight. In some cases, there is also profuse diarrhea. If the loss of weight reaches 20%, death follows within 24 hours. This is preceded by convulsions or paralysis. During necropsy, inflammation and edema are found in the ileum and the jejunum portions of the intestine. In some cases, bleeding and mucosal ulcerations may also be present. Hepatic coccidiosis The liver form of coccidiosis affects rabbits of all ages. The disease is characterized by lethargy, thirst, and wasting of the back and hindquarters, with an enlargement of the abdomen. Abdominal X-rays show that the liver and gallbladder are enlarged. This form of coccidiosis can manifest in two distinct ways. Firstly, it can progress over the course of several weeks, resulting in a chronic state. Alternatively, it can lead to a more rapid outcome, with a mortality rate of up to 10 days, often preceded by a coma and, in some cases, diarrhea. During the necropsy, the liver, gallbladder, and bile duct were found to be distended and enlarged. The liver's surface was covered with white nodules, and the protozoa were identified in the liver and biliary ducts. An impression smear of the liver revealed the presence of coccidia. Secondary infection can lead to their presence in the nervous system, and the disease is often accompanied by secondary bacterial infection, in particular by Escherichia coli.

DiagnosisCoccidiosis is a challenging condition to diagnose. It can be diagnosed through various methods, including fecal flotation to identify oocysts, or under a microscope to count coccidiosis per gram of feces. However, distinguishing coccidian oocytes from the rabbit-specific yeast Cyniclomyces guttulatus can be difficult. If tests confirm the presence of E. intestinalis, E. flavescens, E. irresidua and E. piriformis, treatment should start immediately TreatmentThe treatment of hepatic coccidiosis is challenging, and the disease may persist indefinitely. The anti-coccidiosis treatment is only effective for rabbits infected since 5 to 6 days. Even if the treatment is successful, mortality and diarrhea will persist for several days. Relapse can be observed after 1 or 2 weeks. Robenidine hydrochloride is well tolerated by rabbits, but its regular preventive use over the last 20 years has raised resistance of e.g. E. media and E. magna toward this compound. Further drugs used to treat the parasite include: Sulfonamide and trimethoprim antibiotics have proven efficacious in the treatment of coccidiosis. They should only be used to cure the disease, never as a preventive measure. The most effective drug is sulphadimethoxine (0.5 to 0.7 g / liter water). It is the well tolerated by pregnant and nursing does. Other sulpha drugs include: · sulphaquinoxaline in drinking water: 1 g/litre; · sulphadimerazine in drinking water: 2 g/litre. · Salinomycine (Bio-Cox®); · Diclazuril (Clinicox®); · Toltrazuril (Baycox®), 2.5 to 5 mg/kg (higher doses cause anorexia and decrease in size of fecal droppings), twice, repeat after 5 days. Treatment is best administrated to all the rabbits during a minimum of 5 days. The treatment should be repeated after 5 days. Treatment of the environment is important (e.g. 10% ammonia). Water crocks and feed hoppers should be disinfected and remain free of rabbit feces. When treating a carpet, vacuum first in order to further penetration of the anticoccidial product. During treatment of the environment, rabbits should be kept in another part of the home to avoid the danger of contact with the products and possible intoxication. PreventionBranches and leaves rich in tannin, such as willow, hazelnut, oak, ash, fruit trees, and eventually pines, are effective in preventing coccidiosis. Prior to providing a twig for chewing, it is essential to verify that is not toxic to rabbits. Additionally, the tree must be free from chemical or pollution exposure, such as that associated with major roadways.. AcknowledgementsAll my gratitude to Prof. Richard Hoop (Institut für Veterinärbakteriologie, University of Zurich), Dr K. Hermans (Kliniek voor Pluimvee en Bijzondere Dieren, University of Gent, Belgium), to Michel Gruaz (Switzerland) for the permission to use their pictures related to coccidiosis in rabbits. Further InformationArafa MA, Wanas MQ. The efficacy of ivermectin in treating rabbits experimentally infected with Eimeria as indicated parasitologically and histologically. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1996; 26(3):773-80. Atta AH, el-Zeni, Samia A. Tissue residues of some sulphonamides in normal and Eimeria stiedai infected rabbits. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 1999; 106(7):295-8. Cere N, Humbert JF, Licois D, Corvione M, Afanassieff M, Chanteloup N. A new approach for the identification and the diagnosis of Eimeria media parasite of the rabbit. Exp Parasitol. 1996; 82(2):132-8. Coudert P., Licois D., Drouet-Viard F., Provôt F. 2000. "Coccidiosis". In: Rosell J.M. (ed), (Enfermedades del conejo), vol.II, chapter XVI, pp 219-234, Mundi-Prensa Libros, Madrid, Spain. Licois D, Coudert P, Bahagia S, Rossi GL. Endogenous development of Eimeria intestinalis in rabbits. J Parasitol. 1992; 78(6):1041-8. Manger BR, 1991a Anticoccidials. In: Veterinary Applied Pharmacology & Therapeutics (GC Brander, DM Pugh, RJ Baywater & WL Jenkins, eds) Baillière Tindall, London (UK); pp 549-552, 1991 Pakandl M, Drouet-Viard F, Coudert P. How do sporozoites of rabbit Eimeria species reach their target cells? C R Acad Sci III. 1995; 318(12):1213-7. Pakandl M, Licois D, Coudert P. Electron microscopic study on sporocysts and sporozoites of parental strains and precocious lines of rabbit coccidia Eimeria intestinalis, E. media and E. magna. Parasitol Res. 2001; 87(1):63-6. Peeters JE, Geeroms R. Efficacy of toltrazuril against intestinal and hepatic coccidiosis in rabbits. Vet Parasitol. 1986; 22(1-2):21-35. Renaux S, Drouet-Viard F, Chanteloup NK, Le Vern Y, Kerboeuf D, Pakandl M, Coudert P. Tissues and cells involved in the invasion of the rabbit intestinal tract by sporozoites of Eimeria coecicola. Parasitol Res. 2001; 87(2):98-106. Rommel M, Eckert J & Kutzer E, Parasitosen des Kaninchens. In: Veterinärmedizinische Parasitologie (J Eckert, E Kutzer, M Rommel, HJ Bürger & W Körting, eds), Paul Parey Verlag, Berlin (D); pp 646-662, 1992 Vanparijs O, Hermans L, van der Flaes L, Marsboom R. Efficacy of diclazuril in the prevention and cure of intestinal and hepatic coccidiosis in rabbits. Vet Parasitol. 1989; 32(2-3):109-17. |

||||||||||||||||

e-mail: info@medirabbit.com